At this point, there are few retro Final Fantasy games that I haven’t played at some point in some shape or form. The numerous ports and reissues that made up the earliest days of my JRPG obsession allowed me to experience games that were hard to find and painfully expensive to a high school student in a small town where there were no retro game shops to speak of. Some titles, of course, hadn’t been brought to the modern day, and many of them are still stuck on black and white Game Boy cartridges, much to my chagrin. After all, the prices don’t seem to be going down, and I still don’t have a good retro shop even though I live in a major metropolitan area now.

This is why I jumped as soon as I saw that Square-Enix announced that the Seiken Densetsu Collection was being brought stateside as Collection of Mana, I was ready to launch my wallet directly at them to get a physical copy. After all, I’ve bitched and moaned about not getting this since the year the Switch launched and the Japanese gaming public got this magnificent collection of JRPG classics. It wasn’t for Final Fantasy Adventure that I was excited, though it was a decent bonus. I could get a copy of that online if I wanted it, and it would be in English. I had Secret of Mana on the SNES Classic, so I was covered for that particular classic. But getting Seiken Densetsu 3 in English was only an option if I wanted to pick up a repro cart. This was much cheaper and far more legal. Thanks, Square-Enix. Now update more of your back catalog without doing more pointless ugly remakes.

Of the three games, I had the least to expect from Final Fantasy Adventure, a game that looked like it had more Zelda in its blood than Final Fantasy, but it wasn’t off putting. I love Zelda games. So I eagerly started from the top with the Collection of Mana on the day I picked it up. I wasn’t expecting much from the least praised title in the collection, but I’m happy to tell you that I found myself enjoying it more than I could possibly have expected.

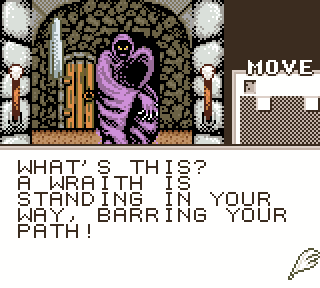

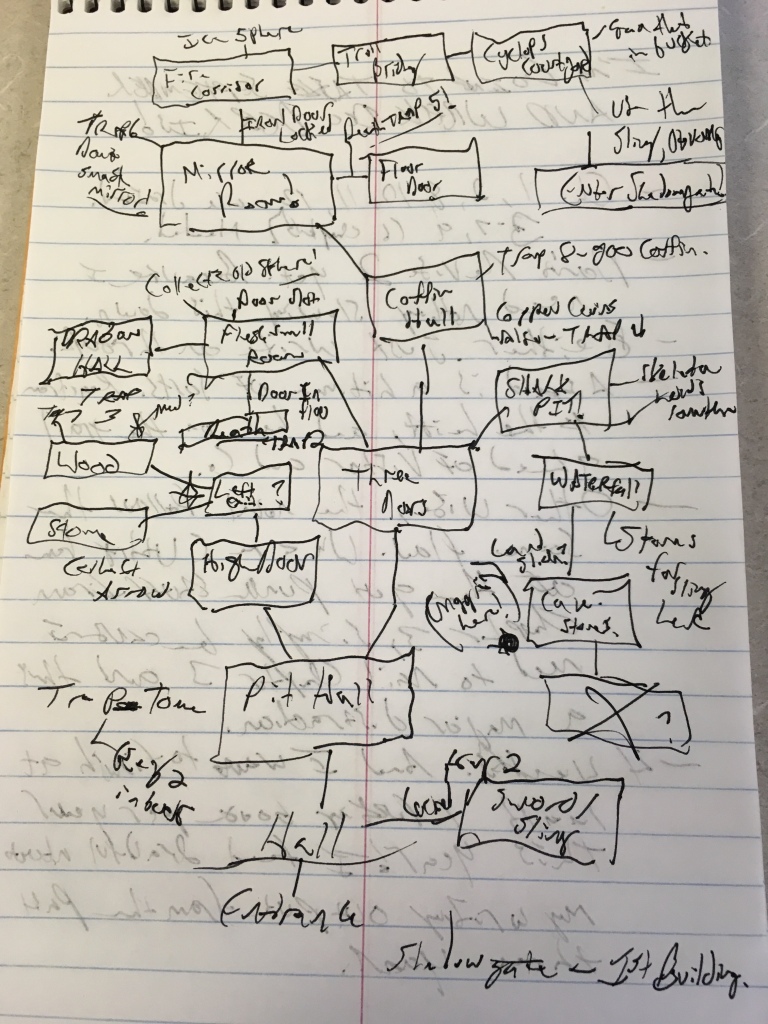

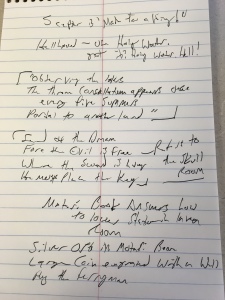

Final Fantasy Adventure opens with a protagonist I called Kain (because FFIV and character limits) busting out of the castle prison and spying on Dark Lord before being cast to the bottom of a waterfall. When he rises, he is tasked with defeating Dark Lord and defending them Mana Tree. You might be wondering why I didn’t put a “the” in front of those Dark Lords but that’s how the game handles his name.

The story is far from deep. Link’s Awakening would eventually become a gold standard for storytelling on Nintendo’s white brick, but the adventure feels grandiose thanks to early 90’s grade Squaresoft melodrama and a well designed world map that takes you through winding paths between story beats and dungeons alike. Each section of the adventure is bite-sized to meet the normal play demands of an old Gameboy game and even allows players to save anywhere, which neuters the difficulty spikes for those of us who save frequently. This isn’t to say that the game is hard, but it’s definitely nice to have the option.

What makes Final Fantasy Adventure special is how it tries to live up to its namesake. The original Japanese title of Seiken Densetsu includes the Final Fantasy Gaiden subtitle, a tie to the revered franchise that seems to have been dropped for Secret of Mana and each subsequent title in the series. Moogle status effects, the hunt for a chocobo, and old school Final Fantasy mainstay super weapon Excalibur make for decent window dressing, but it’s the sense of desperation that drives home the Final Fantasy vibe. Early attempts at “serious” storytelling in Final Fantasy were marked by frequent character deaths, the ongoing dominance of the villain over the actions of the hero, and blunt melodrama – mind you, I think the melodrama is a feature of the genre rather than a bug. Meeting the guardian of the Mana Tree at the scene of her mother’s death is a moment that plays like a tiny echo of any character death in Final Fantasy II.

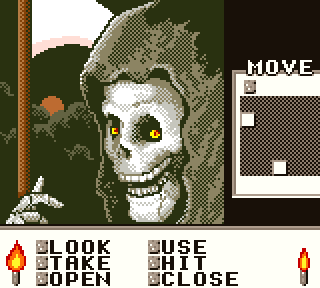

As I’ve mentioned before, gamers who cut their teeth on early Zelda games will be ready for the basics of combat in Final Fantasy Adventure. Players use the D-Pad to navigate around monsters and evade projectiles, and attack with a variety of weapons. In addition to this, there is a meter that fills up over time that increases the amount of damage that an attack can deal. This increases in speed as players level up. Leveling up allows the player to allot points to different stats. It’s a simple enough system of progression, and doesn’t give much room for experimentation, but such is to be expected of an early Gameboy JRPG, unless I’m unaware of a game, and in that case please let me know. Anyone new to this game and system but have played Secret of Mana will be surprised by how slow the meter is at the start. It’s barely worth allowing the meter to power up early on, but as the game draws to its conclusion, it becomes necessary to wait for the heavier damage of a full meter. Thankfully, the meter fills quickly by this point. In addition to melee weapons, guest characters will jump in and out of your party and reward your progress with a variety of magic spells

A standout feature of this game is a delightful score full of catchy melodies that I’m still humming two weeks later. I was thrilled to discover that there does exist a full CD soundtrack for this game. This is one of the best Gameboy soundtracks I’ve ever heard. The somber intro over the story text sets the tone of the game and there isn’t a single bad track to follow it.

I have a reputation for being a SquareSoft snob, and it’s rightfully earned to be honest. I hold up their work in the 90s over other examples of the genre, and harp on about how I wish Square-Enix would make games as charming and engaging on a near daily basis. I’m pretty sure the modern Final Fantasy fandom wishes I would shut the hell up and get out of their circle. A portion of these people probably think that it’s nostalgia that drives my obsession with classic SquareSoft, and that probably explains some of it, such as my love for Final Fantasy VIII despite it’s flaws.

But it isn’t nostalgia that made me love Final Fantasy Adventure. It’s a tightly made adventure with all of the hallmarks of a classic entry in the series. It’s not complex, but it does what it sets out to do with aplomb. I don’t have nostalgia for Final Fantasy Adventure because I’d never had the opportunity to play it until now, as an adult, and it’s a game that has aged beautifully.

Instead, Final Fantasy Adventure set me off on my journey through the Seiken Densetsu series in the best way possible, with a gem of a handheld game that now holds a place among my favorite Gameboy titles, a change that hasn’t occurred in a very long time.

I am aware that there is an iOS remake of Final Fantasy Adventure, as well as the GBA remake Sword of Mana. I’ve not played either of these games, and I don’t need to. I will probably play Sword of Mana in time, but as it stands, I wholeheartedly recommend the original Gameboy title over either remake.